Biodiversity is rapidly declining worldwide. The reasons are commonly known: climate change, overuse, land-use changes, and pollution. Ecological systems are increasingly losing their capability of buffering adverse environmental conditions. Understanding the dynamics of such processes and developing models to predict future ecosystem responses in order to positively influence them has, therefore, become all the more important. A priority program of the German Research Association (DFG) is dedicated to this mission. Ursula Gaedke, biologist and Professor of Ecology and Ecosystem Modelling at the University of Potsdam is the program coordinator.

Uncontrolled growth in the office. A huge yucca covers the window. The green of the botanical garden in the middle of the park of Sanssouci catches the eye. What a workplace for a biologist studying the biodiversity of ecosystems!

Gaedke’s office bustles. The professor stands at a flipchart with a student and explains the trajectory of an experiment. Shelves filled with books reach the ceiling. A table stacked with files, studies, and manuscripts dominates the middle of the room, in-between a heavy handbook that has nothing to do with biology. It is a guide for managers of joint research projects, which has been an indispensable tool for Gaedke since she started coordinating a DFG priority program.

Scientific teams from all over Germany are researching the interplay of biodiversity and ecological dynamics using aquatic communities as model systems. Their aim is to examine how food webs are able to adapt to altered conditions caused by climate change, such as the role played by the existing biodiversity and whether it can be preserved. Gaedke says the impact of the adaptability of natural populations and communities under altered environmental conditions is severely understudied. Experiments and mathematical modelling will now help develop new theories.

To make it all more concrete, Gaedke takes me to several climate chambers in the basement of the institute. Flasks stand on shelves. They are full of algae cultures, which are eaten by rotifers, paramecia, and other creatures. Ambient conditions can be varied during the experiment, and the organism’s flexibility can be studied. The feeding of the “small-animal zoo” takes place three times a day, says the biologist, pointing to a flask a nutrient solution of 10-20 Brachionus sericus per ml. These rotifers are identifiable as floating zooplankton upon closer examination. Choosing these tiny creatures as model organisms allows the researchers to trace dynamic processes in fast cycles. Such small organisms sometimes reproduce several generations in only a day.

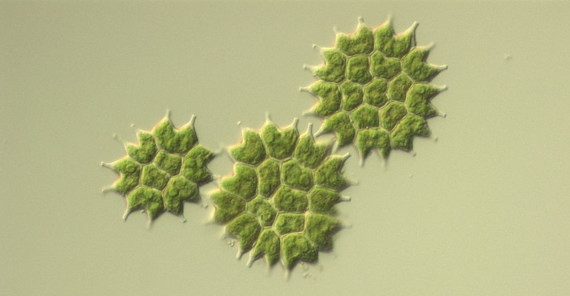

“Understanding how food webs respond to changing conditions is not easy. The interaction between the individual organisms is extremely complex.” Gaedke gives an example: If many micro-crustaceans are in the water, water fleas for example, the number of edible algae declines. They start to protect themselves by forming clusters and sticking together in colonies. They can ingest less nutrient salt in these clusters, making them less competitive at high densities. Other algae defend themselves through phenotypic changes by forming long appendages. “This comes at a price,” says the biologist. “Such a strategy uses energy that could be used for growth.” On the other hand, predators, i.e. the water fleas and other crustaceans, are able to overcome the algae’s protection strategy. Predator and prey are permanently adapting to each other.

The researcher is interested in how such dynamic systems respond to environmental influences. “Less edible algae remaining in the water means lower biodiversity. When environmental conditions change, the ecosystem can hardly respond. It gets stuck,” says Gaedke. The situation is different if the community is diverse and, as a result, variable and adaptable, allowing the system’s dynamics to change. “The solution is a compromise between defense and growth. This maintains biodiversity.” Especially important in this compromise is the type of dependence, the biologist stresses.

The joint research project she is coordinating hopes to improve our understanding of the feedback loop between biodiversity and the adaptability and robustness of ecosystems to be able to better predict and manage responses to disturbances. So far the research has assigned, static traits to specific species independent of environmental conditions. The new models will take into account functional traits for the first time, e.g. edibility of prey and the selectivity of predators that may change over time. The researchers are conducting 20 individual projects with lab and field experiments and developing new theoretical concepts. Gaedke, who is a mathematician as well as a biologist, demonstrates on the computer model that the curves of the constant interplay of mutual adaptation are not as regular as previously assumed. Functional traits have yet to really be taken into account. Any possible scenario can be modeled, however, only when the models correspond to the real measured data. “We therefore ensure a permanent comparison: Experimental data is included in the model, which then is rechecked in the experiment,” says Gaedke. The hope is to develop a tool that enables researchers to predict how ecosystems respond to climate change, for example. Time is short, the researcher warns, “because if we lose biodiversity, we will lose the ability to adapt.”

The Researcher

Prof. Ursula Gaedke studied biology and mathematics in Oldenburg, Texel, and Oxford. In 1988 she earned her PhD in ecological theory in Oldenburg. In 1995 she habilitated in the field of analysis and modelling of pelagic food webs at the University of Konstanz. Since 1999 she has been Professor of Ecology and Ecosystem Modelling at the University of Potsdam.

Contact

Universität Potsdam

Institut für Biochemie und Biologie

Maulbeerallee 2, 14469 Potsdam

E-Mail: gaedkeuuni-potsdampde

The Project

Flexibility matters: Interplay between trait diversity and ecological dynamics using aquatic communities as model systems (SPP 1704)

Duration: 2014–2021

Funded by: DFG Priority Program

Text: Antje Horn-Conrad, Translation: Susanne Voigt

Online-Editing: Agnes Bressa

Contact Us: onlineredaktionuuni-potsdampde