Code & Culture Lecture Series

Upcoming talks

Prompting for Biodiversity: Visual research with generative AI

Who: Sabine Niederer (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences), Gabriele Colombo (Polytechnic of Milan)

When: 9. Februar 2026, 17:00 CET

Abstract

This talk introduces ‘prompt design’ as a research approach to studying visual generative AI, setting it apart from ‘prompt engineering’ practices that focus on producing aesthetically pleasing or technically polished outputs. We will outline several strategies for visual research with generative AI: ambiguous prompting for bias research, reverse-engineered prompting and evocative prompting for machine critique, comparative prompting for cross-model analysis. We demonstrate these strategies through a case study on how visual generative AI represents the topic of biodiversity, which finds that models tend to promote idealized and stereotypical representations of biodiversity, privileging certain species while omitting indicators of biodiversity loss.

Previous talks

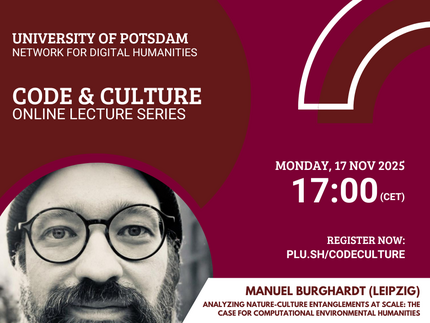

Analyzing Nature-Culture Entanglements at Scale: The Case for Computational Environmental Humanities

Who: Manuel Burghardt (University of Leipzig)

When: 17. November 2025, 17:00 CET

Abstract

This talk explores how environmental issues can benefit from computational approaches in the humanities. I will begin with a brief introduction to Environmental Humanities (EH), a field that seeks to understand nature-culture entanglements and address environmental challenges such as climate change by drawing on humanistic perspectives, narratives, and histories. I will also outline the core ideas of Digital Humanities (DH) and highlight existing work at the intersection of EH and DH. A central point of my argumentation will be that the DH is often described as a "big tent," ranging from tool-based scholarship to interpretive digital media studies to more computational, data-driven approaches. While this latter strand – often called Computational Humanities (CH) – has developed rapidly in recent years, it has not received a lot of attention within EH. The second part of the talk therefore argues for a Computational Environmental Humanities (CEH): an approach that uses computational methods to study environmental discourse, cultural imagination, and human-nature entanglements at scale. Drawing on recent examples and emerging techniques, including large-scale language models and multimodal information extraction frameworks, the talk will outline research opportunities and illustrate how computational methods can extend rather than replace interpretive traditions in the environmental humanities.

Introducing Computing Writing: Why Literary Studies Matter

Who: Katherine Bode (Australian National University)

When: June 23, 2025 12:00 CEST

Abstract

This talk introduces Computing Writing, a book (nearing completion) that argues computing and writing are not separate realms but entangled material-semiotic practices. The book identifies a “paradox of representationalism”: while literary scholars reject the idea that writing simply represents pre-existing reality, many embrace this framework for computing and data, treating them as instrumental tools of discovery or destruction, rather than participants in meaning-making.

Drawing primarily on feminist Science and Technology Studies, the book develops a performative approach to literary studies (including CLS) through “diffractive writing.” This approach explores patterns of understanding that emerge from, rather than preceding, relations of diverse writing practices, including with text and data. Working across and combining literary theory, textual studies, and literary history and criticism, alongside the collaborative data project, A Writing-Reading Interface (AWRI), it argues that literary studies, including CLS, matters as a rich tradition and ongoing practice of exploring and extending the realities and possibilities of writing-world relations.

Genres of existence: Network graphs, genre theory, and the metaphysics of fictional things

Who: J.D. Porter (Price Lab, University of Pennsylvania)

When: May 12, 2025 17:00 CEST

Abstract

While analyzing literary genre as it appears in a large dataset scraped from the book review website Goodreads.com, my colleagues and I have consistently found evidence supporting literary critic Catherine Gallagher’s observation that “the primary categorical division in our textual universe is between ‘fiction’ and ‘nonfiction’”. This is especially clear in our network graphs of the co-occurrence of the tags users assign to books, since community detection algorithms find a fiction/nonfiction divide even at very low granularity. Yet the network does not just show a divide; it also shows that the two categories are deeply connected—a tag like “France” or “family” might show up in a history or a mystery, a cookbook or a romance novel. Genres in this graph are not discrete islands, but densely interconnected regions in a single continuous space. If the distinction between fiction and nonfiction can be understood as a genre difference—as philosopher Stacie Friend has argued on other grounds—then we ought to treat them as part of a continuous single space as well. This might have interesting metaphysical implications, since the big difference between fiction and nonfiction seems to be their ontological stances (one refers to things that are “made up”, the other to things that are “real”), and continuity between the two categories suggests a similar lack of hard-and-fast divisions between real and made-up things. In this talk, I explore the implications of this idea, drawing on ongoing digital humanities investigations of genre, philosophical deployments of network metaphors, and scholarship on the metaphysics of fictions, literary and otherwise.

Literary Computing of US-American Romance Novels

Who: Svenja Guhr (Technical University Darmstadt)

When: March 12, 2025, 17:00 (UTC+2)

Abstract

This talk explores the application of literary computing to contemporary popular fiction, focusing on the Romance series Men Made in America. By employing scene-segmented unit comparisons, it analyzes the representation of domestic space and character sound across the corpus, offering new perspectives on the structural and thematic elements of this popular genre.

Digital Humanities — an Ancient History

Who: Prof. Dr. John Dawson, Head of Head of the Literary and Linguistic Computing Centre (LLCC) at the University of Cambridge from 1974 to 2009.

When: Nov 12, 2024, 04:00 PM (CET)

Abstract

The discipline now known as Digital Humanities has a long history. It began in 1946 when Roberto Busa began preparing a concordance to the works of Thomas Aquinas by mechanically sorting punched cards. The first of 56 volumes, prepared with help of many other labourers, was published in 1974. There are, of course, alternative historiographies of Digital Humanities, which take other events as starting points, but they all agree that DH has a long and diverse history.

The Literary and Linguistic Computing Centre (LLCC) at the University of Cambridge was established in 1964 and had to devise innovative methods for inputting, storing, and analysing text of many types and in several alphabets.

John Dawson was Head of LLCC from 1974 to 2009. During that time, advancements in computer storage, software techniques, and printing technology revolutionised Digital Humanities, but they also posed many new challenges for humanists. Two examples:

- In 1977 Chinese characters could only be drawn as simple line-drawings on a graph plotter, and there was no established way to sort and print the mixture of Chinese and English required for a Chinese–English dictionary.

- Concording the Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot required a large amount of computer store, three magnetic tapes, and 45 minutes of computer time on a mainframe computer. The Concordance had to be sent on magnetic tape to be printed on a Monotype typesetter at Oxford University.

The talk will show how some of these problems were overcome. Many of the techniques have been made redundant by modern technology, but lessons can still be learnt.

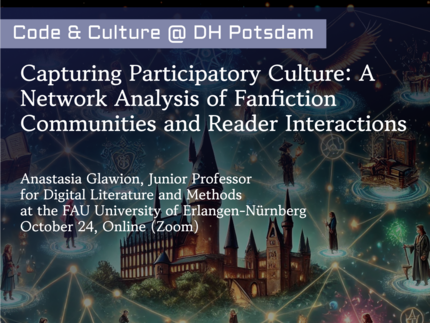

Capturing Participatory Culture: A Network Analysis of Fanfiction Communities and Reader Interactions

Who: Anastasia Glawion, Junior Professor for Digital Literature and Methods at the FAU University of Erlangen-Nürnberg

When: 24. Oktober, 18:00 AM CEST

Abstract

Over the past 20 years, fanfiction writing has been on the rise. This fan-driven practice presents an ideal case for digital literary studies, as the texts are digitized, widely available, and challenge the status quo of the canon. Many fanfiction scholars have underlined the importance of the participatory aspect in studying the phenomenon. In this presentation, I show how interactions on fanfiction websites can be investigated through metadata-based network analysis. This approach provides fresh insights into textual reception and reader engagement, while offering a more comprehensive perspective on how fanfiction communities interact with texts and reshape them. As a result of this process, various interpretive communities emerge, each with its own dynamic. Some span across multiple fandoms, while others demonstrate different perspectives on a single canon, such as communities in the “Harry Potter” universe where a distinctive cluster focused on Hermione becomes visible.

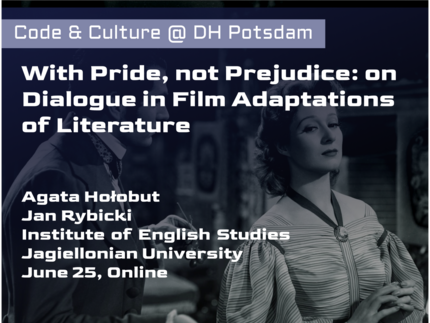

With Pride, not Prejudice: on Dialogue in Film Adaptations of Literature

Who: AgataHołobut, JanRybicki, Institute of English Studies, Jagiellonian University

When: 25. Juni, 10:00 AM CEST

Abstract

The study of film adaptations of literature has gone through a variety of approaches from the early evaluative reviews of the 1950s through comparative analyses of the 1970s to a more intertextual view of the phenomenon starting with the 1990s. Our research looks both into quantitative and qualitative discussion of film dialogue and its translations and into the part that words play in film portrayals of various historical eras. This is especially important in films that adapt (or translate) literature as much of the viewers’ expectations is based on their perception of the literary original; at the same time, modern perception of the novels’ and films’ historical settings also come into play.

Quantitative approaches allow a whole series of comparisons between the dialogues of novels and their film “translations” (and into translations of that dialogue into other languages), from simple percentages of direct usage of dialogue (and narrative) to stylometric analyses of word frequencies and other linguistic items. But quantitative analysis can also look at visual elements such as character screen time or camera angle; this can then be compared between various adaptations of the same text and between the adaptations and the literary text in search for similarities and differences of perspective.

We illustrate our research with examples from a variety of adaptations of literature, with particular focus on various Pride and Prejudice films (1940, 2005) and TV miniseries (1980, 1995). Based on selected scenes taken from the four productions we show how recycled, reworked and re-vamped fictionalised dialogue interacts with other elements of the film’s structure to create different interpretations of apparently identical literary characters.

Thinking About Culture (not) as Data

Who: Lev Manovich, Distinguished Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York

When: 4. Juni, 10:00 AM CEST

Abstract

Why do we often approach cultural data using ideas developed in the 18th and 19th century, before digital computers and big data? Can we think about cultural objects and histories without using categories? What can AI see in cultural artefacts, and what it remains blind to? Lev Manovich will discuss what he sees as some of the biggest challenges in looking at culture with computers, and suggest some ways to address those challenges

The cultural code of gender: from binary classes to a complex phenomenon of literary characterization

Who: Mareike Schumacher, assistant professor for Digital Humanities at the University of Stuttgart

When: May 7, 2024, 18:30 CEST

Abstract

Can the two classes "male" and "female" – often understood as a binary either-or distinction – actually be modeled as basic units ("primitives") that can be arranged into complex codes designating all facets of gender in its multiplicity? In this talk, an analogy between the technical binary code and the cultural code of gender is used to test the hypothesis that gender can be seen as a discrete phenomenon constructed through varying combinations of male and female features. Additionally, it is brought into question whether "neutral" should be seen as a third basic unit and whether there might be more “gender primitives”.

The presentation also includes a case study from Computational Literary Studies, in which several corpora consisting of literary texts in the German language are analyzed. In the study, gender roles such as ‘father’, ‘young girl’, or ‘person’ are classified according to basic gender units. By analysis of almost 400 character profiles, typical and atypical gender codes are defined, and a spheric notion of gender is introduced.

The Driving Forces of Literary Evolution: Tracing the Causes of Cultural Change with the Price Equation

When: April 2, 2024, 18:30 CEST

Who: Oleg Sobchuk, researcher at the Department of Human Behavior, Ecology and Culture, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Germany

Abstract

Does literature progress “one funeral at a time”, as Max Planck famously claimed about science? Is the change mainly driven by the turnover of “generations”, or cohorts? Who contributes more to change in literature and arts – “old masters” or “young geniuses”? And how can we separate the different causes of cultural change?

A trendline spanning a period of time is one of the most common graphs in the computational humanities. Often, such a trendline is explained with a single causal mechanism: a cause C is driving a trait T over a period P. For example, the proportion of negative words (T1) during the 20th century (P1) in literature is increasing due to “negativity bias” (C1). Or, the proportion of abstract words (T2) in the 19th century (P2) is growing due to urbanisation (C2). On the surface, this approach may look sufficient but, under the surface, there are rocks: not only there could be multiple causes, but also different parts of the trendline may be driven by different causes. In computational humanities, there is no effective method for “dissecting the trendline” and uncovering these hidden causal mechanisms.

The scholars of evolution, however, do have such a method: a simple and elegant – and famous – equation that was suggested by the mathematician George R. Price over 50 years ago, known as “the Price equation”. It allowed biologists to uncover the potential driving forces behind evolutionary change. The forces behind literary – and, more broadly, cultural – change are still little known – and much debated. The Price equation can give us the answers.

Buchvorstellung mit dem Autor: „Theatre as Data“

Who: Miguel Escobar Varela (National University of Singapore)

When : Nov 28, 2024, 02:00 PM (CET)

Where: Am Neuen Palais 10, House 9, Lecture hall 1.14

Registration form for online participation: here

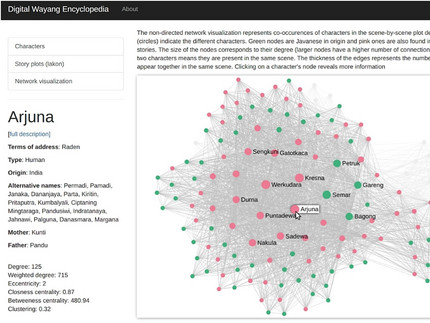

Abstract

In 'Theatre as Data: Computational Journeys into Theatre Research' Miguel Escobar Varela examines the use of the use of computational methods in theatre research. On the basis of examples (not only) from his own research on Southeast Asian theatre, he shows how statistics and visualisations can offer exciting insights into various aspects of theatre studies.