It sounds quite unusual: playing for science. But for the small test subjects whose behavior Boll-Avetisyan analyzes, it is exactly the right research method. “My method is suitable for babies from the age of nine months. From this age on, they can play with the toy,” she explains. “You can test children very early to see if they have difficulties with language. Long-term studies from the field of language development research show that in the case of disorders precursor skills are already not developed during infancy.”

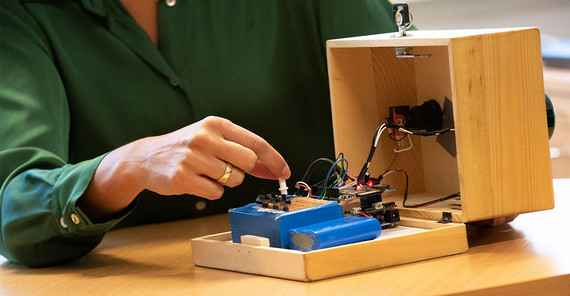

Prof. Boll-Avetisyan developed the play object for studies in the BabyLAB at the University of Potsdam and has since patented it: Externally, it is nothing more than a wooden box with two green push buttons. As simple as it appears, the interior structure of the box is exciting. The electronics inside ensure that tones sound at the touch of a button. It also measures how often and how long the child presses which button when it perceives certain sounds, words, and intonations. Small, compact, portable, and with an easy-to-understand application – this makes the box well suited for mobile use.

Supporting preventive medical examinations

Boll-Avetisyan would like her toy to be used in the future during the pediatricians’ U6 checkup (early diagnosis and prevention examinations), that is for infants 10-12 months old. “We wanted to have a tool that can determine a status during the regular visit to the pediatrician.” Until now, the little ones are only being tested for their language development at the U7 checkup, when they are about two years old. Among other things, they have to demonstrate a certain vocabulary during this examination. It is tested which words the children understand, which ones they use and whether they can form short sentences with them. “But not all language disorders come down to a small vocabulary,” Boll-Avetisyan explains.

Those who stand out at U7 checkups are categorized as “late talkers” for the time being. Of these children, about 50% are able to catch up on their language deficits. According to Prof. Boll-Avetisyan, this ambiguous finding, the threat of therapy costs, and the fear that early treatment could create an awareness of the problem in both child and parents leads to health insurance companies not supporting measures that start at this early age. Parents only have the possibility to support their children privately with the help of the “Heidelberg Parent-Based Language Intervention”. According to this program, they should, for example, repeat sentences in everyday conversations or support them with other actions. The prerequisite for a prescribed therapy is a diagnosed speech disorder. Currently, however, the diagnosis is made at the age of four at the earliest. “Risk screenings at both U6 and U7, whose results are combined, could lead to an earlier diagnosis,” Boll-Avetisyan says. “A speech disorder cannot be cured but can be treated well. However, treatment methods are more effective the earlier you begin.”

At the beginning of the project, which was awarded the FöWiTec Prize of UP Transfer GmbH in 2021, Prof. Boll-Avetisyan and her team tested which preference the babies have for stress patterns of artificial words. The result was clear: “The children would rather hear the German stress pattern than one that does not occur frequently in their mother tongue.” This means that, even as babies, they prefer a stressed first syllable, which is typical in German.

Language preferences put to the test

With the help of the two push buttons on the toy, Boll-Avetisyan is able to record how the children react to different phonetic stimuli as pairs of opposites - and prompt these reactions, so to speak. In the future, the researcher wants to use it to investigate further reactions to other stimuli: Do the babies prefer spoken words to noise? Do they prefer real words to artificial words? Are they more likely to respond to speech directed at the child than to how adults talk to each other? Whether one can clearly assign a disorder based on these preferences can so far only be roughly determined. Too little research has been done on language development disorders.

However, it is known how the clinical picture manifests itself. “Children with developmental language disorders do not understand long sentences well or have to search for words for a long time,” she explains. “If their everyday life is characterized by misunderstandings and frustration, the affected children can develop mental illnesses that accompany them throughout their lives.” How many symptoms the children have varies a lot. Prof. Boll-Avetisyan therefore wants to raise awareness of the disorder among parents, in kindergartens and schools, and provide the respective education.

So, it is even more important to make the test toy fit for the pediatrician's practice: Boll-Avetisyan wants to prepare a guideline for the practitioners that lists criteria and standard values that facilitate risk identification. In addition, the toy will be equipped with a display so that doctors can easily evaluate the results. Before it can be launched on the market, the researcher still has to validate it for medical purposes. For this, she would like to seek support from the colleagues in Potsdam.

So far, almost 100 babies have taken part in her study. In the first step, the researcher is concentrating on monolingual, German-speaking children who are nine months old. In the future, however, she would also like to collect data from bilingual test subjects and follow the development of all the children interviewed over a period of years. Especially bilingual children with speech disorders are still rarely recognized because speaking difficulties are attributed to a natural delay due to the influence of several languages.

It was proven that the babies enjoyed playing with the box. Some engaged with it for up to a quarter of an hour. Even in the first study, it was shown that the children pressed that button for longer, which the researchers expected them to prefer. In concrete terms, this means that the toy works as they hoped. Now it is only missing a name.

FöWiTec Award of the University of Potsdam for the Promotion of Knowledge and Technology Transfer

Potsdam Transfer – the central institution for innovation, start-up, and the transfer of knowledge, and technology at the University of Potsdam – supports up to five application-oriented research and development projects each year with a total of 50,000 euros. Potsdam Transfer supports the development of the idea and, together with UP Transfer GmbH, ensures that the projects can be successfully implemented.

https://www.uni-potsdam.de/de/potsdam-transfer/transferservice/foewitec

The Researcher

Prof. Dr. Natalie Boll-Avetisyan studied linguistics at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and Utrecht University. In 2012, she received her doctorate from the Utrecht Institute of Linguistics. Since 2010, she has been working at the University of Potsdam. In 2019, she was appointed Junior Professor for Developmental Psycholinguistics and is now researching early language acquisition.

Email: nataliepboll-avetisyanuuni-potsdam

This text was published in the university magazine Portal Wissen - One 2023 „Learning“ (PDF).