1. Crime series “Tatort” or “Polizeiruf 110”?

Neither nor. I do not watch violence on TV for entertainment.

2. What fascinates so many people about crime every Sunday?

The suspense that comes from being able to watch dangerous taboo-breaking in the safety of their living room. And people may think they can learn something useful for their own lives. Studies show that regular viewers of crime fiction significantly overestimate the actual incidence of murder and manslaughter in their country. In line with the well-known “cultivation theory”, one can say that crime fiction affects the viewers’ perception of the world.

3. Violence as entertainment: How does research into media use perceive this phenomenon?

Most research takes a critical view of depictions of violence in the media, a view that is supported by a broad base of empirical data. The aim is not only to demonstrate the connection between the portrayal of violence and aggressive behavior in the media, but also to show conclusively the psychological processes that can explain this connection. People who regularly watch murder and manslaughter on television or kill increasingly realistic avatars on screen become desensitized to violence, learn that violence can lead to success, and more easily activate aggressive thoughts and feelings in real life. Although consumption of media violence is, of course, not the only risk factor for aggressive behavior, the magnitude of the effect is similar to most other recognized risk factors.

4. From what age should we start promoting media literacy in our society?

As early as possible because even the youngest children are avid media users. In the beginning, the main thing is to limit consumption so that there is enough time for other activities that are fun. Of course, parents also have to make sure that the content is suitable for children. There must be no room for violence, even - or especially - if it comes wrapped in humor.

5. Is there a perspective that gives aggression a positive connotation?

In everyday language, the term “aggressive” is sometimes used with a positive connotation, for example in the context of sports competitions in the sense of “forceful” or “assertive”. In social psychology, however, there is a general consensus that aggression is defined as a behavior carried out with the intention of causing harm to others, and it is thus a form of negative, antisocial behavior.

6. Are there any differences between humans and other mammals with regard to aggression?

The intention of inflicting harm, which is the critical defining criterion of human aggression, presupposes a complex cognitive process in which actors anticipate the potentially harmful consequences of their behavior and decide to carry it out anyway. This process cannot be simply transferred to animal behavior. Konrad Lorenz’s popular steam-boiler model also underlines this point. It may fit animal behavior but is unsuitable for explaining human aggression for several reasons. It is interesting, however, that animals have also developed mechanisms for constraining aggression within a species, such as submission rituals in fights over hierarchy.

7. How do you yourself compensate moments of aggression?

Even if I don’t always succeed, I try to draw on my theoretical knowledge to stay calm and downregulate anger in such situations - for example, by activating positive thoughts and feelings that are incompatible with anger, or by trying to understand the situation from the other person’s point of view.

8. How can aggression be demonstrated empirically?

Purposefully triggering behavior that harms others is not justifiable from an ethical perspective. Therefore, in experiments, one must rely on proxy measures of aggression that reflect an intention to harm, e.g. by (supposedly) giving another person a negative evaluation on a task that is important to them. Furthermore, aggression can be observed in natural contexts, e.g. at school, through self-reports or in victim surveys, and from archival data, such as crime statistics.

9. Is aggression a phenomenon that differs regionally?

There are big differences between cultures, but also between historical epochs. Aggression is a social construction, i.e. cultures and eras decide by social consensus which behaviors they want and don’t want to consider aggressive. Even today, different cultures consider it the right of men to physically chastise their wives. It also took our society until 1997 to recognize marital rape or rape of male victims as a crime against sexual self-determination.

10. Is sexual aggression gender-specific?

Yes, it definitely is. The likelihood of acting in a sexually aggressive manner, i.e. causing another person to engage in sexual activities against their will, is considerably greater for men than for women. But men, too, can become victims of sexual aggression - as our research also shows - from women as well as from men. This problem should not be ignored.

11. What particularly triggers a young adult to develop sexual aggression?

Early adulthood is a phase of development in which young people try many new behaviors and challenge rules. Alcohol consumption plays a critical role in more than 50% of sexual assaults, but so does inexperience in communicating sexual intentions and respecting boundaries.

12. Which topic is the focus of your current research?

We are currently conducting the third data wave to evaluate the DFG-funded prevention project KisS (“Competence in Sexual Situations”), which we developed in my team. We hope to find that participants in our program, mostly students of the University of Potsdam, are less likely to experience sexual victimization or engage in sexually aggressive behavior themselves over the two-year follow-up period and perform better with respect to a number of competences than participants in the control group.

13. Are there any new topics in 2020 that you are dealing with in aggression research because of the pandemic?

Indeed, I am often asked these days what contribution aggression research can make in the time of the pandemic. On the one hand, I think it can contribute to a better understanding of the burden and its consequences. For example, by showing under which conditions frustration, which we all experience to a considerable extent, triggers particularly strong anger and aggression or what makes it easier to tolerate. This can inform approaches to mitigating the negative effects, for example that frustration-related anger may be reduced if the frustration is seen as unintentional or inevitable. I am also concerned about the rise in domestic violence. Here, aggression research can provide the theoretical knowledge to anticipate problematic developments and include these social costs of the pandemic in the consideration of measures.

14. What are the three most pressing current questions regarding protest violence?

I think they relate very much to the Covid19 pandemic protests, and I would mention three questions: (1) What effective strategies can we use to dissuade people from believing in fake news and conspiracy theories and from purposefully breaking rules that are considered reasonable based on the available evidence? (2) How can we avoid a potentially explosive polarization of society in terms of how to deal with the Covid19 threat? (3) How many personal restrictions and how much sacrifice can people be expected to endure before violent protests take place on a large scale, as we have already seen in some places in Europe?

15. Where is violence more firmly rooted - on the left or on the right?

This cannot - and should not - be set off against each other. Violence must always be condemned, and both left-wing and right-wing ideologies produce enemy images that legitimize violence and undermine social peace. Therefore, society must be alert to violence from both of these somewhat simplistically juxtaposed directions. It is undisputed, however, that the prevailing social climate plays an important role in determining how much attention is paid to violence coming from the right and from the left. It can hardly be denied that too little attention has been paid to the danger of right-wing violence in the recent past. And our country is not the only one where we can we see how this can lead to the strengthening of movements that divide society.

16. What is the biggest difference between domestic violence and violence in the public sphere, for example at demonstrations?

The difference is that domestic violence happens covertly, often remains undiscovered for a long time, and happens between people who should be united in love and care. This makes it particularly depressing.

17. The first and last demonstration you took part in?

I have always had a difficult relationship with this instrument of bringing about social change, so my participation in a demonstration in the Hofgarten in Bonn against the stationing of nuclear weapons in Germany and the NATO double-track decision in the 1980s was my first and at the same time last activity in this field.

18. What was a key moment in your career as a scientist?

When I realized that there is no other profession in which you are allowed to ask your own questions and set your own tasks to the same extent. I only realized over time the disadvantage that inevitably comes with this freedom – it also implies no clearly defined point in time when the work is done or when you can take a break. Nevertheless, I would say that the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages.

19. What is your favorite quote?

The motto that my grandfather, who was a Latin teacher, gave me, “Suaviter in modo, fortiter in re”, which translates as “Gently in manner, firmly in action”.

20. Who is your role model?

It is difficult for me to pinpoint one specific person here. But following from the motto just mentioned, I would say Prof. Bärbel Kirsch, with whom I closely worked for many years, especially during the time when we established the Department and the Faculty, which was then still called PhilFak II, and who always embodied this attitude for me in an exemplary manner.

21. On campus or better working from home?

I have preferred working from home already before the Corona pandemic, because I find it easier to think and write without being interrupted.

22. Reading the newspaper - in an analog or digital format?

Preferably analog, even though it’s a pity that more and more online articles are disappearing behind a paywall in my local daily newspaper.

23. What does success mean to you?

To bring a task on which I have worked for a long time, and which at times I could not imagine would ever be finished, to a good end, and in such a way that I am still satisfied with the result after some time. I am also hoping for this good feeling for the recently published third edition of my textbook on social psychological aggression research.

24. What was your biggest failure?

It is not easy to make a choice here, but if I listen inside myself, one experience surfaces quite quickly: the fact that a few years ago I didn’t succeed in convincing the university leadership that it is not a good motivational strategy to “reward” the acquisition of a sabbatical from the German Research Foundation, including the funding that came with it, by making me wait an extra year for the next regular sabbatical.

25. What advice would you give to a young researcher?

I would encourage young researchers not to be guided by tactical considerations or external guidelines in their search for topics and in their research programs, but to follow their own interests. I would also encourage them to become part of the international community in their field as quickly as possible, to network with researchers from all over the world, to invest in joint projects, and to take on responsibility as reviewers and editors of journals. For some time, I have been observing with disappointment that this commitment is acknowledged less and less in the incentive structures of my faculty, which I see as a step into provinciality and a bad signal to young researchers.

26. What do you like the most about your profession?

The freedom to define the questions and goals of my research and to be able to investigate them independently and with an open outcome.

27. When was the last time that science has changed your life?

Through the development of digital forms of communication, which enable me to take part in the lives of my children and grandchildren, even over long distances, in real time, and with images and sound. This is particularly important in the current situation.

28. Who would you like to do research with?

With Terrie Moffitt, one of the leading researchers involved in the world-famous Dunedin Study, which has followed a large sample from childhood into what is now advanced adulthood, examining their developmental trajectories in a variety of areas, including aggressive behavior.

29. What discovery would you like to have made yourself?

The discovery of the dramatic consequences a baby’s lack of attachment to a reliable caregiver has for the rest of his or her life. This discovery was made by Mary Ainsworth and John Bowlby in the 1950s and laid the basis of today’s attachment research.

30. How do you create a balance to your work?

Through my family, daily walks and a great interest in soccer, particularly when it comes in the colors of black and yellow.

31. Which book that you have recently read has remained in your memory?

I very much enjoyed reading the novel “Eva Sleeps” by Francesca Melandri, which tells the eventful political history of my favorite holiday region, South Tyrol, in the 20th century interwoven with a multifaceted family story.

32. What are your goals “after the University of Potsdam”?

These include successfully completing my aforementioned DFG-project on the prevention of sexual aggression among young adults and embarking on some new writing projects. And I hope to realize the idea for a project that I’ve had in mind for a long time: a lavishly laid-out illustrated book on the topic of “aggressive cues” to show how ubiquitous and popular violence is in our everyday lives, from pistol-shaped kitchen radios to salt and pepper shakers in the design of hand grenades.

33. In your opinion, does good or evil win in the end?

I think this question is oversimplified. Good and evil will always co-exist, and the balance between the two will vary between people as well as situations, regions, and historical periods. We must work on strengthening the good and removing the basis for evil. As an optimist, I say that this can be achieved by fostering the responsibility of each individual for their families, neighbors, and the community, and as a social psychologist I can think of a number of ways by which this can be achieved. As a realist, however, I must say that many obstacles will have to be overcome on this journey.

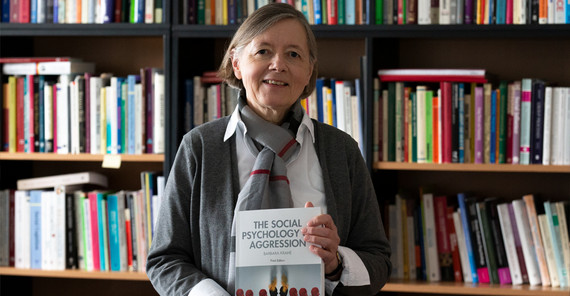

The Researcher

Prof. Barbara Krahé has been Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Potsdam since 1993. Prior to this, she worked, among other places, at the University of Sussex, United Kingdom, for several years. For her achievements in the field of social psychology, in particular aggression research, she received the German Psychology Prize 2015. She was President of the International Society for Research on Aggression (ISRA) from 2018 to 2020 and is currently Past-President until 2022. She will retire from her position at the University of Potsdam after the winter semester 2020/21.

Mail: kraheuuni-potsdampde

The german version of this text was originally published in the University Magazine Portal Wissen - Eins 2021 „Wandel“.