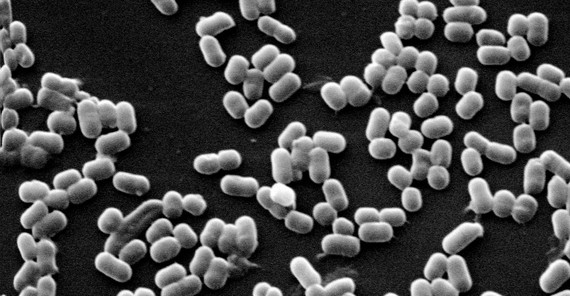

They are on the skin, in the intestine and on the teeth. Microorganisms inhabit our body. The colon in particular is an ideal place for microbes. One gram of intestinal content contains about ten trillions of bacteria. Michael Blaut, researcher at the German Institute of Human Nutrition and Professor at the University of Potsdam, studies the influence of the so-called gut microbiota on human health as well as the influence of nutrition on the intestinal flora.

Intestinal bacteria – non-professionals would not immediately associate anything positive with this word, but only very few microbes in the intestine cause diseases. Most of them support an essential bodily function: digestion. The microorganisms – in addition to bacteria these are also viruses and single-celled organisms – produce many enzymes that the human body could not produce alone. Many components of our food would not be broken down or made available without the gut microbiota. It influences not only digestion and metabolism but many other functions of our body. Allergies, obesity, and colon cancer – researchers assume that, in addition to other factors, the gut microbiota influences these and other diseases.

Prof. Dr. Michael Blaut, who heads the department „Gastrointestinal Microbiology“ at the German Institute of Human Nutrition (DIfE), has been dealing with the microbiota in the human intestine for 20 years.

“Every microbiologist knows: The type and place of bacteria depends very much on the respective conditions,” explains the researcher. In ecosystems in the external environment as well as in the human intestine, microorganisms occupy those ecological niches which provide them with the optimal growth conditions. Several thousand types of bacteria have been identified that inhabit the human digestive tract. Each of us hosts at least 160 types. Microbial colonization begins at birth. The exact composition of the organic community in humans varies considerably. We partially decide which microorganisms are in our intestine: with our nutrition, because what we eat is ultimately available to the organism in our intestines. The dominating type of bacteria depends on how rich our food is in fat or carbohydrates. “The most important food source for bacteria are fermentable carbohydrates that we cannot digest,” Blaut explains. The more varied our food, the better the preconditions for a diverse bacterial community.

Tests on germ-free reared mice without any microorganisms on the skin and in the intestines indicate that intestinal bacteria influence more than the digestion in the host bodies. They are extremely susceptible to infections and even minor infections overstrain their immune system. “The immune system exists with all its components but is not fully developed. We now know that the exposure to bacteria is essential for the immune system to fulfill its functions,” says Blaut.

Chronic inflammatory intestinal disorders, like Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, also show the direct connection between the immune system and the gut microbiota. The number of cases of these two diseases has been increasing continuously for years. Those affected suffer from diarrhea, bleeding, and pain. “It is now known that apart from a genetic disposition the outbreak of these diseases require additional environmental factors,” Blaut explains. The exact causes, however, are still unclear, but there is some evidence that this also involves the microbiota. Michael Blaut and his research team at the DIfE examine which intestinal bacteria may aggravate intestinal inflammations under certain conditions.

The researchers use mice whose microbiota they specifically influence. There are eight types of bacteria in the animals’ intestines. Mice with an intact microbiota are usually resistant against a salmonella infection. In the absence of a certain bacteria group in their intestines mice that come into contact with salmonellae react with an inflammation. The researchers even went a step further and added another, usually harmless bacterium to salmonella-infected animals. This triggered additional inflammations in the intestines. The composition of the intestinal microbiota obviously influences the course and severity of an intestinal infection. “We are currently examining what are the reasons behind,” Blaut says. It only seems to be clear that a disturbed microbiota changes the function of the epithelial barrier. When substances cross the mucosa in an uncontrolled manner, highly specialized cells of the immune system react with inflammations.

Blaut has always been fascinated by unicellular organisms that although being so extremely small are capable of tremendous metabolic performance. “The microbiota influences our physiology. Despite highly developed methods that are now available we are not able to understand many of the acting mechanisms,” he sums up. The researcher sees nutritional recommendations from a completely different perspective. “A well-balanced nutrition with a wide range of fruit and vegetables, many wholemeal products – these are exactly the substances that provide versatile substrates for the bacteria.”

The mission of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Research Potsdam-Rehbrücke (DIfE) is to conduct experimental and clinical research in the field of nutrition and health. About 80 scientists and 65 PhD students of nutritional science, biology, medicine, and chemistry in seven departments primarily research molecular causes of nutrition-dependent diseases and develop new strategies for their prevention and therapy. They develop nutritional recommendations based on scientific findings. A particular focus of the DIfE is the research on diabetes, cancer, hypertension, and obesity.

Text: Heike Kampe

Online-Editing: Agnes Bressa

Contact Us: onlineredaktionuuni-potsdampde