From Musicology of the Earth to Computational Ethnomusicology of Georgian Music

My first encounter with Georgian vocal polyphony took place in 2011. At that time, I knew nearly nothing about Georgian music, nor did I have much experience in multi-voice singing. My practical musical education by then had consisted of four years of flute lessons as a child and ten years of classical guitar training as an adult, followed by thirty years of practice as an amateur instrumentalist. In addition, as a University student and in order to satisfy my interest in musical theory, I took courses in musicology for two years. As my main topics, however, I was studying geology and physics to become a seismologist, a profession which by now I have exercised for more than thirty years at Universities and Research Centers in a number of different countries of the world.

Seismologists sometimes like to describe seismology as „Musicology of the Earth“, a metaphor which carries a surprising amount of truth in it. The physical mechanisms of sound generation within the Earth and within musical instruments – including the human voice - are often quite similar, as are the computational tools with which audio recordings and seismic recordings can be analysed today. What has long fascinated me and has influenced the research of some of my students and myself alike is the similarity between sounds generated within the Earth and musical instruments.

In this context, I discovered „reframing“ of problems, in other words seeing problems from the perspective of a different discipline, as a very powerful strategy for my research. Reframing the generation of volcanic tremor signals for example as a problem of musical acoustics, allowed the interpretation of the pitch of these signals in terms of properties of the volcano.

The similarity of volcanic and acoustic signed also turned out to be very interesting in a musical context. In 1999, the composer Wolfgang Loos and myself published the CD “Kookoon: Inner Earth”, for which seismic signals from volcanoes where used as raw sound material.

Shortly after the turn of the century, I had reached a point in my music making where I felt that the music which I could create with the guitar, even after more than 30 years of practice, was lacking something essential. Despite all the technical abilities which I had developed over the years, I only rarely felt deeply connected with the sounds of my instrument.

During my first year at high school, the music teacher, whom I remember as a very serious looking man in a black suit, was looking for new members of his choir. Every boy had to stand up in front of the class and was examined regarding his „usability“. Being a ten year old shy little village boy and being quite scared in front of all the city kids, I was not able to produce any useful sound and was consequently sorted out. This memorable experience fortunately did not kill my love for music, but it definitely generated a feeling that singing was not meant for me. However, a little more ten years ago, in order to find out if I could get a more intimate connection with music which I would make, I was ready to prove this feeling wrong.

My first singing teacher was Sigurd Bemme in Berlin, who leads a male a-capella choir specialised on traditional polyphonic Alpine music, and who with great patience and creative exercises guided me through the ups and downs of my first two years of singing education. In 2011, he introduced me to Georgian vocal polyphony, by taking me and my wife Marie-José to a singing workshop led by Frank Kane. At that time, I did not know what impact this would have on my life.

A number of non-Georgian musicians and music lovers have eloquently described the beauty of Georgian Vocal Polyphony. The strong impression it had on me is beyond what I am able to express in words. Adding to the immediate fascination for this music was the fact that the protected atmosphere, which Frank Kane was able to create in his workshops, let me experience an intensity of music making which I had been searching for for a long time.

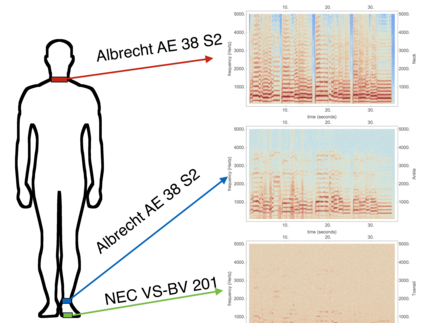

As a seismologist, having worked with vibrations and waves for most of my professional life, I was also intrigued by Frank ´s way of conceptualising Georgian singing as “vibrational sharing”. I immediately started to wonder about the physical aspects of these mysterious vibrations. Soon after our first meeting, we jointly started to perform some “seismologically inspired” experiments to quantitatively investigate the generation of body vibrations during singing. It quickly became obvious that with special sensors body vibrations during singing can be recorded all over the body. Now, my scientific curiosity was triggered!

Trying to read everything I could find on Georgian music, I eventually learned that Susanne Ziegler, for me the most knowledgeable person about Traditional Georgian Music in Germany, was actually working at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, not even half an hour from where I live. She agreed to meet and since then has generously shared insights from her long standing experience. She also introduced me to the recordings of Georgian singers in the phonogram archive in the museum, to the works of the pioneers of ethnomusicology in Berlin (Stumpf, von Hornbostel, Nadel, etc.) as well as to classical ethnomusicological research practices. Becoming aware of the challenging problems related to classical transcription of Georgian music into western staff notation made me realise that the recordings of body vibrations during singing could possibly help to solve a problem of ethnomusicological field work, namely to obtain clean recordings of singer’s voices in terms of pitch, intonation, and voice intensity, while they are singing together in their natural singing environment.

During those first years of my involvement with Georgian singing, my wife Marie-José and myself tried to participate in as many singing workshops as seemed physically possible. In 2013, we also went to Georgia together for the first time to participate in a workshop with the charismatic singer and choir leader Tamar Buadze in Kakheti, which left unforgettable memories of spontaneous singing in public places.

Since then I have spent more than half a year in different regions of Georgia ands on different occasions. The following year I attended (as an observer) the 7th International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony in Tbilisi, where, despite having no credentials in ethnomusicology other than my enthusiasm, I was generously invited to join the group of scholars. At that meeting, I was also introduced to the legendary ethnomusicologist Simha Arom. Best known for his work on African Polyphony and Polyrhythm, he had also started to work on Georgian music, trying to decipher its musical grammar using score analysis. Some time prior to the symposium, I on the other hand had experimented with score analysis using mathematical tools which I was familiar with from my geophysical work and had shown the results to Susanne Ziegler and Frank Kane. Both immediately suggested me to talk to Simha Arom, which happened during the symposium’s field trip to Uplistsikhe. It turned out that indeed we had lots to talk about and that this meeting was the beginning of a stimulating collaboration which still continuous today.

By 2014 it had become clear to me, that singing and my musicological research of Georgian music had become more than just a hobby. As a consequence, I applied for a research leave of absence from my position as professor of geophysics. Together with singer and ethnomusicologist Nana Mzhavanadze, who I had met earlier that year, I proposed to pursue a seismologically inspired ethnomusicological field trip to Georgia to test if the idea to use recordings of body vibrations during singing could have any serious use. Meeting Nana had caused yet another shift of gears in my relationship with Georgian music and my own music making. Nana with her beautiful voice and her incredible musicality, being able to direct two voices with her arms (one of them behind her back), while singing the third voice, represents for me the essence of what I have come to believe polyphonic music is all about. And, to my great surprise, it turned out that we could communicate very well on ethnomusicological issues, despite the enormous differences in our musical backgrounds.

My proposal was fortunately granted and in the summer of 2015, Nana and myself started to work together on our first joint small field experiment. One of the most memorable evenings during that trip was at the Chamgeliani house in Lakhushdi, when - besides enjoying the generous hospitality of the Chamgeliani family - we were able to record Islam Pilpani, Murad Pirtskhelani and Gigo Chamgeliani using larynx microphones. These and the other recordings taken in Svaneti during that pilot study demonstrated for the first time the benefits of body vibration recordings for ethnomusicological research.

Encouraged by the results of this first study, I applied for larger field expedition to record Svan village singers in Svaneti and Svan settlements in other parts of Georgia, again together with Nana Mzhavanadze. The reason for choosing Svaneti as the target region for our field trip was our believe that if one wishes to understand traditional Georgian vocal music, there is no way around the understanding of Svan songs, since presumably the first stages of Georgian vocal music development have been preserved in them. In addition, I had fallen in love with this beautiful region and the hospitality of the people. So during the summer of 2016, Nana Mzhavanadze and myself, together with Levan Khijakaze, and with the financial support from the University of Potsdam, spent three exciting months in the field. The tangible result is now a unique new collection of audio, video, and larynx-microphone field recordings of traditional Georgian singing, praying and lamenting, which is now open to all researchers of Georgian music (see here). The intangible results are even more precious to me, memories of beautiful landscapes and incredible people who temporarily shared their lives with me and taught me again and again that singing together is an invaluable treasure.

When I got involved in ethnomusicological research, I eventually realised that reframing, which I had used as a research tool to tackle seismological problems from the perspective of musical acoustics, also works well the other way round. Thinking of the recording of singing voices as a seismological observation problem during one of Frank Kane’s singing workshops was what got it all started to find a new way to analyse the singing voice and to get around classical transcription.Applying mathematical graph models to musical scores was originally done for the pleasure of trying them out. They have now become an important tool in the context of the work with Simha Arom to analyse and visualise chord progressions in collections of musical score, which provides another example for the power of reframing.

But there is still another layer to the story. During our first field expedition in 2015, we also did some test recordings with Malkhaz Erkvanidze and some members of his choir Sakhioba. Malkhaz, in addition to teaching me a number of beautiful songs, also generously shared his insights about his theory of the Georgian Musical System. He convinced me of the crucial importance of historical recordings of old master singers from the last century, regarding all questions of historical performance practice and tuning. In particular, the more than one hundred chants sung by Artem Erkomaishvili, which were recorded at the Tbilisi State Conservatory in 1966 in what is now called overdubbing technique, seemed to offer a phantastic opportunity to apply some computational analysis tools which I knew from seismological signal processing , in order to obtain insight into the musical thinking of this giant of traditional Georgian singing oft he last century.

Therefore, in order to learn more about modern computational approaches to audio- and music processing, in October of 2015, after my return from Georgia, I attended the International Society for Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR) Conference in Malaga/Spain. During one of the evening concerts, I happened to sit right next to Meinard Müller, professor for semantic audio processing at the University of Erlangen and one of the world leaders in music processing. When, back in Berlin, I was struggling with my first attempts to make sense oft the Artem Erkomaishvili recordings, I remembered the brief discussion with Meinard in Malaga and decided to ask him for advice. This turned out to be another very consequential decision. Not only did he have ideas on how one could computationally extract pitch information from these recordings, he also had an excellent student to work on this problem in the framework of his master thesis, Sebastian Rosenzweig.

The results of the subsequent analysis of Sebastian's results clearly document the systematic deviation of Artem Erkomaishvili's tuning system from equal temperament and impressively demonstrate the importance of harmonic intonation changes at certain positions in the songs and for certain harmonic intervals such as the fifths, unison, the octave, and the ninths.

In addition, Sebastians's thesis was the start of yet another very fruitful and still ongoing collaboration which eventually resulted in a joint research proposal between Meinard Müller and myself on „Computational analysis of traditional Georgian Vocal Music" which to our great joy was funded by the German Research Council. This led to an incredibly stimulating cooperation between Meinard's group in Erlangen and my group in Potsdam which ran between 2018 and 2022 (extended due to the pandemic). In addition to our core team members, it temporarily involved colleagues from Paris (Simha Arom, Florent Caron-Darras, Frank Kane) and Tbilisi (David Shugliashvili, Ana Lolashvili) with whom we joined forces on selected topics. For more information on the GVM projects see here.

In the course of my involvement with Traditional Georgian Music as a music lover and a researcher, I have become convinced that new technologies and computational methods can be very useful for ethnomusicological research. Not as a replacement to classical approaches, but as a complementary perspective, of course. For me, computational ethnomusicology has become the perfect research field which allows me to combine my passion for science with my love for traditional Georgian music. For the future, I hope that these new developments can contribute to a better documentation and possibly even a better understanding of some aspects of this precious cultural heritage.